Neoptolemos Michaelides

I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.

‘When I was young, my uncle brought me a vine leaf and placed it on the palm of my hand and said, “Touch this leaf”. It had a very delicate feel. You have to be sensitive to everything around you. You have to be sensitive to the sun, to the light, to the shadows, to the water, the wind. Today, we ignore all these elements, we are inhuman, we violate nature. This worries me…

I was 12 years old when my father announced that he was to build a house on a family plot of land outside the village where he was born. I had never seen the site before, but from what I had been told, it was an olive grove of trees that were hundreds of years old.

In preparation, he decided to cut them all down, levelled any sign of undulating landscape, and poured gravel over the remaining green: all ready to go! Now he had to find the architect. After all, his best friend had convinced him that he should build a proper house and not a prefabricated unit with basic facilities, as was his original plan. The same friend was wise enough to insist on recommending a man he knew and praised as ‘the best architect’. There was not much convincing to do: my father has always valued his friend’s opinions, and shortly afterwards he assigned this architect the task of building him a home. Carte blanche.

Many years later, I learned that great houses are created through a relationship of trust between the client and the architect. However, only now do I know that what my father really had in mind was literally providing this man with a blank piece of paper, a naked plot of land where any sign of its landscape history had been erased.

Neoptolemos Michaelides could not have wished for a worse curse. Around his own house, he never pruned a single tree. ‘It’s as cruel as amputation’, he used to say.

Neoptolemos had a very unusual relationship with nature—at least, one that was unfamiliar to me, though very intriguing. He once told my father that he had something to give him. I remember him pointing at a location on the map by the side of a small road, on the way to the Troodos Mountains. One day Neoptolemos drove with my father to this spot and said, ‘Here is your present! Take it home and I’ll tell you where to place it’. It was a huge rock of red jasper. It was like an act of adoption, ‘borrowing’ a piece from nature and repositioning it, with exactly the same painstaking skill that ancient Chinese scholars had used before. The rest of the rock’s family was in his own home, the smaller siblings that he had managed to ‘rescue’ and relocate years earlier.

I had never experienced the art of viewing to such a degree.

Shortly afterwards, my father returned the gesture, offering Neoptolemos and his wife, Maria, various objects ranging from a bronze, plastic desk clock with his company’s logo on it to African souvenirs, like a hand-carved wooden bust of a woman, which he had picked up on one of his travels to Burundi. ‘Look!’—Maria grabbed my father’s attention one evening when we went to their house for a drink. ‘Look at the beautiful shadow it casts on the wall, like a crawling panther ready to attack’; the ordinary statue had acquired a whole new value, becoming a gobo next to the accidental light that her husband had informally, but beautifully, put together.

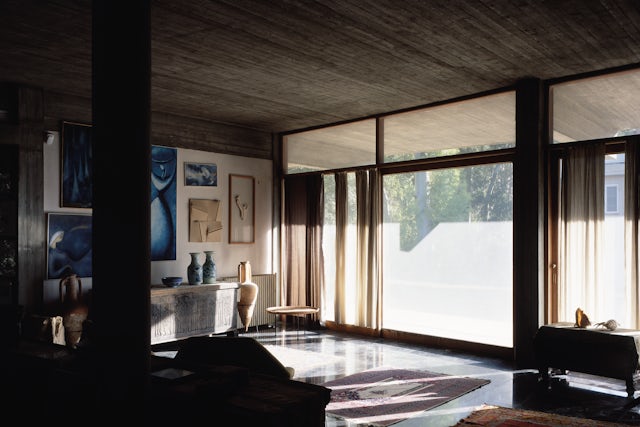

From that day on I realised that nothing had ever been thrown into its place accidentally. Each object in relation to others around it and everything in relation to the human scale and the environment, with curated views from carefully positioned seats in the austere setting.

I remember the first time I walked into their home, after an evening invitation from him and his wife, entering a dimly lit space, just enough light to be able to move slowly through the different spaces. I immediately thought that this was a beautiful way of slowing someone down, adjusting your pace to appreciate an environment of such beauty. My father immediately complained that everything was so dark, in a tone that almost required more lights to be installed for the next time we would be around, when Neoptolemos answered softly, ‘There is a reason why there’s the night and there’s the day, and we should not try to turn one into the other’. I sometimes think that his statement was the reason I became a designer of lights.

We started to walk up the marble cantilevered steps, the rail being nothing but the trunk of a young tree that became thinner to the grip as you reached the upper levels. And standing vertical was the main support, another tree, wider at its base, thinning out to almost a point, rising well above the last rail, a few feet below the cast-concrete ceiling in wood-grain relief. It was like the ones Giuseppe Penone carved out years later from these old beams, exposing the young tree within before it grew and was cut square. Only that the passage of time was no longer suggested through the removed layers, but through the appreciation of the younger part as you climbed up.

With the same type of wood were these beautifully simple display cabinets, full of fossils, shells, stones, and minerals, found on their travels or collected locally over the years. I remember going on an excursion with Neoptolemos; with the task of finding crystals, we searched and searched for hours without luck, when suddenly he picked up a perfectly formed round stone that just about fit his palm and offered it to me. ‘Here, a true sphere!’ he said. ‘You can’t beat nature!’

His search for purity was clearly embedded in his refined environments. He always believed that ‘the symbol of culture is the mathematical minus -, and the symbol of barbarity is the plus +’.

It was the time that our opinion started to ‘matter’, my brother and me in our early teens, when my father asked us what requests we had from the man who was to build our house. We suddenly felt important, grown up, and bombarded him with spontaneous, superficial ideas. Anything that came to our minds, probably images borrowed from the homes of fictional characters we admired. I remember specifically asking for a pitched roof, one with an extreme pitch that created this ‘amazing’ space inside. We were both present when our father passed on these requests, when the small gentle man looked at us and just smiled. We never got anything we asked for, only the swimming pool; after all, we shared the same passion for water. Years later, I heard him advise the younger generation in one of his talks ‘to learn the place where we come from, the real one. Not the one with borrowed foreign structures, with roofs of 60 degrees inclination, in a land where we pray for rain’.

‘The British have a very wise saying: doctors bury their mistakes, architects can't; these structures say a lot about the people who built them’.