HOME AS A PASSAGE OF TIME

Michael Anastassiades lives as he works, in a paredback, deeply considered manner, a way of life reduced to its essence. Home is a platform for the designer to understand how to create an environment. It’s largely furnished with pieces he’s created specifically for the three-storeyed space above a former clothing shop in Waterloo in central London, where he’s lived for the past 22 years. Best known for lights, Anastassiades also designs furniture and objects like the polished brass coffee mill he uses every day. One benefit of the lockdown earlier this year was that the time spent sequestered at home was a perfect contemplative period to test and reconsider his designs. Not just by using an object but, as he says, by “living with it physically, seeing it and reading it”. Some are prototypes or early versions of a stool or a light, others are exhibition pieces and there are new production pieces such as the Vertigo lamp hanging above his solid walnut dining table desk.

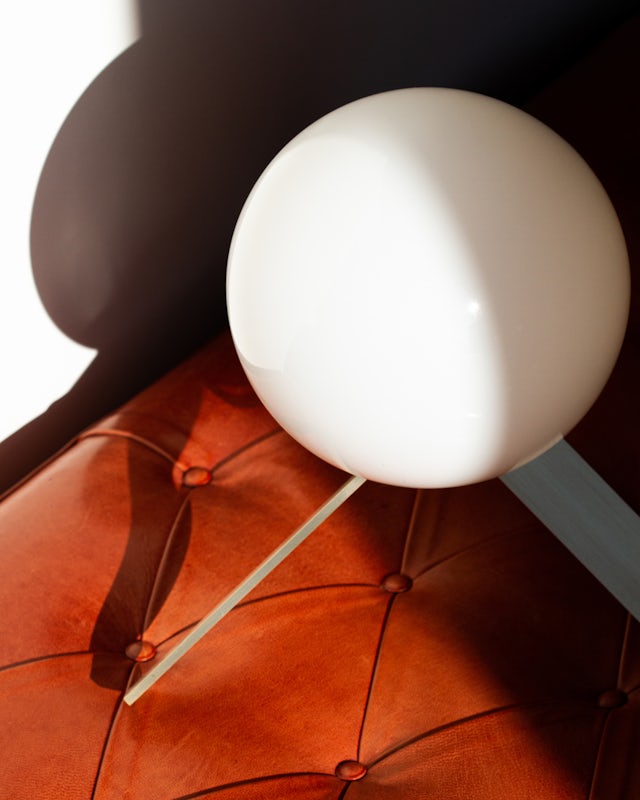

On the rare occasions Anastassiades brings home something he hasn’t designed, he calls it “hosting” another designer’s work and spends inordinate amounts of time carefully selecting it to ensure the scale and proportion relate perfectly to its intended space. In his inner sanctuary on the top storey where he retreats to read, he has three pieces by Kaare Klint, the founding father of Danish modern design. The pair of Addition sofas and footstool were a “gift to myself ”, says Anastassiades, who saved for and bought them in 2010 to mark his 40th birthday three years before.

“I love those pieces so much; it gives me so much joy to look at them. The scale is so right, everything is perfect, the colour, the whole patina of the leather and how it changes over the years are incredible.” He bought the mahogany and Niger leather-upholstered pieces from the legendary Danish cabinetmaker Rud. Rasmussen just before the business was sold in 2011. He’d haunted the workshop of the family-owned business since the early 2000s, amazed to find such a place in the heart of Nørrebro in central Copenhagen where it had been making furniture since 1875. “I remember visiting the wooden storage where they kept all the wood and the leather upholstery space; it was a gem, like the most precious thing I had ever seen.”

A Cypriot, Anastassiades trained as a civil engineer at Imperial College London before taking a masters in industrial design at the Royal College of Art, graduating in 1993. The next year he founded his studio and started working with a joiner in Suffolk with whom he still collaborates. “Every single piece made out of wood in my own home is made by him,” he says. That sort of relationship was fundamental to the Danish design canon he has long admired. Cabinetmakers such as Rud. Rasmussen collaborated with creators such as Klint and their products were credited to both.

Ever since he became critically aware of design, Anastassiades has been a huge fan of the Danish movement and it’s a strong reference in his work. He says he’s attracted to an apparent simplicity that is underpinned by a sophisticated understanding of how an object can be reduced. Primarily though, he’s interested in how the great Danish designers or architects, as he prefers to describe Klint, used historical references as their starting point rather than claiming what they were presenting was completely new. “The idea that somebody comes and says this is something new, I don’t believe it’s true,” he says emphatically.

Klint (1888-1954) set up the department of furniture design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, mentoring a generation of students to take an analytical approach to furniture design that drew on history and diverse cultures to create modern functional pieces.

Although they were cutting edge, a lot of what is now considered iconic Danish modern furniture had strong historical references. Hans J. Wegner’s Wishbone chair evolved from his fascination with Chinese 18th century furniture and Børge Mogensen was inspired by English Windsor chairs and the Shaker movement for his simple pieces, notably the Spanish chair.

“I really believe that in design, or generally in the world, nothing is new,” says Anastassiades. “All ideas existed at some other time, maybe the technology was not the same but had the conditions been the same then the similarities would have been even greater.” That the Danish modern designers were able to come up with a completely new idiom to suit their contemporary way of life at the same time as referencing layers of history, is what makes their work so appealing, and ultimately timeless, he says.

“Looking at design through the times, this negotiation that the designer has always had with society and the values that define society has been very important in the end result.”

Anastassiades believes that what you contribute as a designer, is a re-interpretation to give something a contemporary context. The strength of Danish modern is that even though they were designed in the 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s they are still relevant today. “This has been my biggest fascination with Danish design,” he says.

Two years ago, he collaborated with Ole Høstbo of classic furniture specialist Dansk Møbelkunst to create the Halfway Round furniture series. The monolithic table, solid wooden stool and curved screen in Oregon pine build on the Danish design heritage but are in no way nostalgic. For the designer and the dealer, it was the culmination of a friendship forged over their shared passion. But it was also a departure for each of them: Høstbo joked it was the first time he’d worked with a designer who was alive after dealing in 20th century Nordic classics for more than 25 years, while Anastassiades is mostly known as a lighting designer. “I wanted to learn something different and this is why furniture made sense,” he says.

Anastassiades worked closely with a Copenhagen-based cabinetmaker, resuming the relationship that was a feature of Danish modern. “I wanted to bring the qualities and knowledge of the cabinetmaker into the designing process, this profound sense of the material and its possibilities.” He says it became a three-way conversation between himself, the cabinetmaker and Høstbo whom he calls a “historian”. “There was a lot of back and forth; the pieces have to be constructed in a certain way, all in solid wood, and in Oregon pine because I didn’t want them to feel too precious.”

As a prelude, Anastassiades curated exhibitions in the Paris showroom of Dansk Møbelkunst, positioning his designs with pieces he selected from Høstbo’s collection in the gallery space. “Nothing new was introduced but the way of seeing things was more important for me than the objects themselves,” says Anastassiades. It is this seeing and reading of a piece that is at the heart of his work, especially those created under his own name brand where his ideas are expressed in their purest form. Although he designs them in the context of his home – the proportions of the highly architectural Vertigo light, for example, relate to the structural central column that divides the house into quarters – his great skill is that they can transcend that space and work well in larger or stylistically diverse environments.

“If you look at the objects that are currently in the collection, they have presence but manage to remain discreet. They’re very much inspired by the space that I live in and they’re intimate like the spaces they occupy. Proportion and scale are everything in design.”

As with the best of Danish design, Anastassiades aims for timelessness, which he says derives from several inherent qualities. Honesty in the way a product communicates itself, is the most important: “Not trying to be something it isn’t.”

Then there’s aesthetic simplicity, designs that are pared back to the minimum but not minimalist, an expression he can’t abide. Every detail is there for a reason. The design process is about reducing “layer after layer after layer”, to a point where if you took something else away the object would not exist.

Finally, there’s materiality, the qualities of the actual material a product is made of, the honesty in how it is used, and how it ages or develops a patina over time. Everything is handmade in natural finishes. Metals are meant to oxidise. “Material that has a life in the same way as everything should have a life. It’s not a picture or a frozen moment, things change and it’s nice that you allow the material of a product to change.”

Being timeless is about being relevant but not tied to a time. And it’s not static. Like his Klint sofa: inspired by French rococo, designed in the 1930s as versatile and modern sectional furniture, skilfully made in the early 21st century, and ten years later with a patina that only comes with the passage of time. “It is the continuous interaction with time that makes a design timeless.”